Education Has Reached a Sputnik Moment, but Closing the Department of Education Won’t Help

Much has been said recently about the U.S. Department of Education and its purported link to the declining performance of the United States in international education rankings. This narrative, which began as memes on social media, has now made its way into mainstream discussions. The claim is that educational rankings have worsened since the creation of the Department of Education in 1979.

I won’t delve into the distinction between correlation and causation—though, it’s worth noting that the trend may actually point in the opposite direction. There are ways to track test score trends immediately before and after the creation of the Department, but there are other events, both before and after 1979, that likely have a greater impact on these outcomes.

The U.S. education system clearly requires reform and a much deeper level of attention. However, focusing solely on the Department of Education is unlikely to be the solution. For one thing, there is no compelling evidence that the existence of the Department, or its creation, has been a significant factor in the country's relatively low performance in international assessments. This becomes apparent when we examine the historical record.

To illustrate: the first international student assessment of mathematics in 1964 involved just twelve countries. Over the following decades, more countries joined these assessments, expanding into larger and more comprehensive evaluations in the 1980s and 2000s. Today, over 100 countries participate in international student assessments. However, the core group of countries that have consistently participated since the early assessments includes Australia, Chile, England, Finland, France, Hungary, Iran, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Thailand, and the United States—13 countries in total.

This historical context suggests that focusing on the Department of Education as a singular cause of educational decline overlooks a far more complex and multifaceted issue. The conversation about U.S. educational performance would be better served by looking at broader factors and seeking a more nuanced understanding of the challenges at hand.

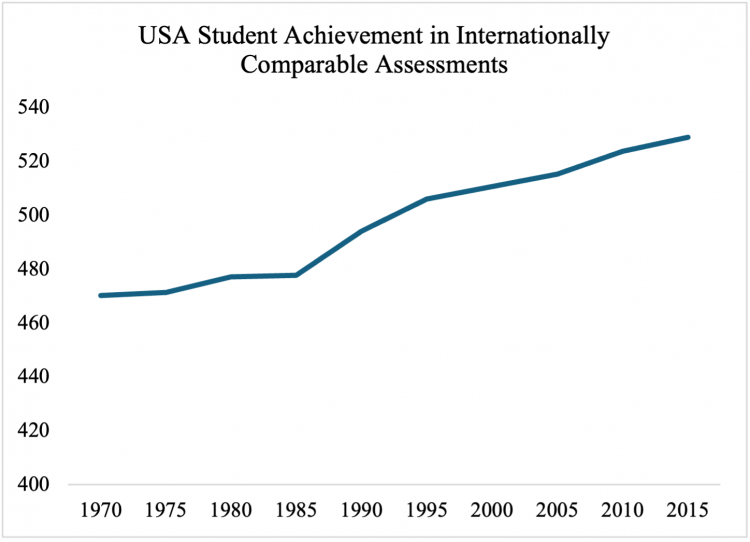

We amassed and harmonized the international test scores going back decades and put them into five-year buckets starting in 1970. This allows us to see early rankings and trends over time. Of the 12 countries, Japan was the best performer in 1970 and remained on top by 2015. The United States was 6th in 1970 and climbed to number 4 in 1980 and 1995 and ended up in 5th place in 2015. However, despite the ranking, the US scores increased by 59 points, almost 2/3 of a standard deviation; or, in other words, by two and half years’ worth of learning equivalent.

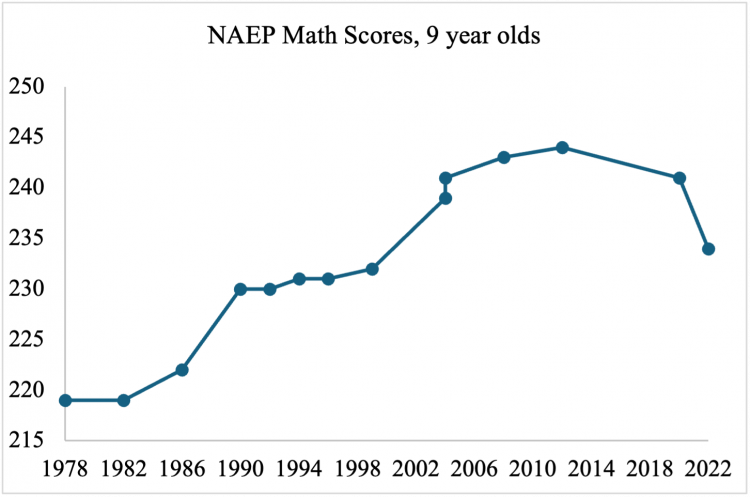

This is confirmed with NAEP data (though on a different scale). There has been a clear and increasing trend after the establishment of the Department of Education.

Another spark that ignited school reform was the 1983 special commission organized by the US Department of Education which released A Nation at Risk. This publication prompted a public response and a shift of policy and practice in the education system. It focused on the quality and quantity of teachers, which it found wanting. Nevertheless, test scores rose soon after.

Sputnik 1, sometimes referred to as simply Sputnik, was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. This major achievement by the US’s major international foe led to some soul search and concrete action by authorities. One of the areas targeted for reform was the education system.

This was seen as a national security threat. Education was targeted for reform and attention. This spurred investments in science education. Congress responded with the National Defense Education Act, which increased funding for education at all levels, including low-interest student loans to college students, with the focus on science.

Education is in crisis. Not just here but almost everywhere in the world. Test scores were on the decline before the pandemic, but COVID-19 school closures exacerbated the problem and we are yet to recover.

The question now is whether we are ready to respond with the urgency and ambition needed to close these gaps. The Sputnik Moment analogy is apt: in the late 1950s, the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik sparked a national crisis in the United States, leading to massive investments in education and innovation, particularly in science and technology.

Are we ready for a new Sputnik Moment? Will we use the crisis in education as a call to action, pushing for bold reforms and innovative solutions? Or will we continue to let this crisis erode the potential of future generations?